The popular Hidden Lake Trail begins at Logan Pass–the highest point on the Going-to-the-Sun Road as it crosses the Continental Divide. It doesn’t matter how many times I’ve driven the 32 miles from West Glacier or 18 miles from Saint Mary, I always feel a sense of elation and warn myself to never take this incredible gift for granted.

The Going-to-the-Sun Road opens sometime between mid-June and mid-July, depending on how much snow accumulates in the higher elevations. It closes on the third Monday in October. Early snows can close the high elevation sections of the road sooner.

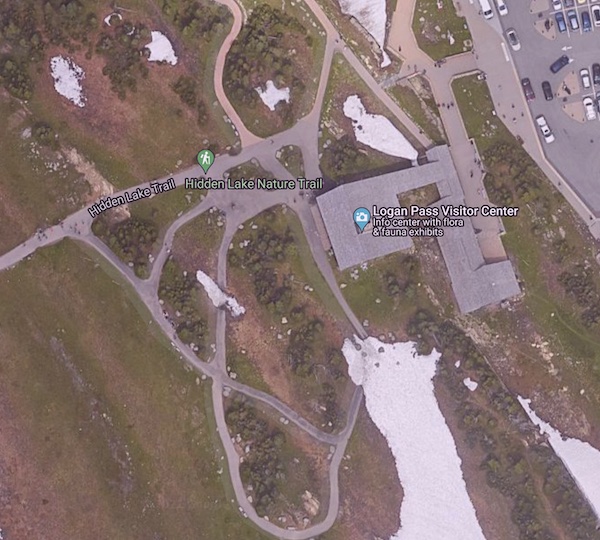

During July and August, it can be an exercise in patience and perseverance finding a parking spot at Logan Pass. If there is no road construction, the parking lot can be nearly full by 6 am some days. The park’s Logan Pass webcam can give you an idea of what you’re in for. Best bets for Wi-Fi are the Apgar Visitor Center and Saint Mary Visitor Center.

Glacier National Park’s shuttles can help resolve the parking issue, but the buses have their own challenges. Check out Glacier’s Shuttle System webpage for the latest on tickets and schedules.

Trailhead

The Hike

The overlook is only 1.4 miles away, but it’s a walk filled with sights to behold, and discoveries to be made.

Here, growing seasons are short and winters long and brutal. After the snow leaves in July, plants have little time to green up, grow flowers, produce seed and begin the dormancy process before they’re buried in snow for eight or nine months.

The subalpine terrain, over which you’ll walk, is fragile. This ecosystem can take a long time to heal if it’s damaged. In fact, some trampling in this area has taken 30 years to recover.2 Knowing that increased visitation would lead to more destruction, the park service built the boardwalk over the lower part of the trail during the early 1970s. That was not without problems.

Trail crews installed timbers treated with pentachlorophenol–a wood preservative used since the 1930s. That leached from the boardwalk and killed surrounding plants. Rightfully, there was a huge outcry and a lot of “we told you so”. The park service fixed the problem by replacing all the material with more benign wood products.1,5

Even with the difficulties, installing the boardwalk was still a wise decision for this environment. Researchers from the University of Montana documented over 1,000 visitors per day using the Hidden Lake Trail to the Overlook.4 Thanks to forward looking park officials, visitors can walk over the sensitive meadows rather than on them.

A Burst of Color

The meadows come to life as soon as patches of ground appear. Glacier lilies are an impatient type. They can push through the last layers of snow, blooming with no hesitation. Various hues of green speckled with blues, purples, pinks, whites, and yellows slowly replace the expanse of white.

The Sculpted Landscape

The Pleistocene epoch or Great Ice Age deserves credit for the spectacularly chiseled mountain scenery in Glacier National Park. It began 2.6 million years ago and ended 11-12,000 years ago. During some of that time, only the tallest mountains in Glacier National Park poked their summits above the massive-valley-filling ice sheets.

The glaciers plucked, scraped, and gouged the mountainsides as the ice flowed to lower elevations. They left behind the sculpted landscape that we value so much today. On this hike, you’ll see the textbook glacial features below.

Horn: a mountain that was bounded on at least three sides by glaciers. Clements Mountain (north of the trail), Reynolds Mountain (south of the trail), Bearhat Mountain (southwest of Hidden Lake Overlook).

Arete: narrow ridge once separating two glaciers. Dragon’s Tail (south end of Hidden Lake), The Garden Wall (northeast of the trail across Logan Creek Valley).

Cirque: amphitheater-like depressions carved into a mountain by glaciers. Hidden Lake lays in a giant cirque

U-shaped valley: rather than a stream or river eroding just the bottom of a valley creating a v-shape, a glacier fills and concentrates erosion from the bottom to the top of the valley. Reynolds Creek Valley (southeast of Logan Pass).

Moraine: rock debris left behind by a glacier. About one mile into the hike, there’s a long 100-foot high gravel ridge on the right. It was left behind by the now non-existent Clements Glacier.8

Glaciers that exist in the park today are more recent, going back only 7,000 years. They reached their maximum during the Little Ice Age, which lasted from the mid-1300s to mid-1800s.3

Four-Legged Residents

Once the plants are up, the plant eaters are on the move and so are those that eat the plant eaters. Columbia ground squirrels, golden-mantled ground squirrels, least chipmunks, hoary marmots, bighorn sheep, mountain goats, coyotes and grizzly bears all use this subalpine ecosystem.

Don’t let the number of people or the closeness of the visitor center lull you into complacency. The park service closes this trail several days during the season when bears and people want to hang out in the same places. Carry bear spray. Know how and when to use it. And it’s a good idea to practice taking the canister from the holster and removing the safety clip to ensure that you can do it quickly. Grizzly bears have a top speed of 50 feet per second. Things can be over in a flash.

Look for hoary marmots and pika where meadows merge with mountain talus slopes. This harsh environment is also home to the Columbia ground squirrel, golden-mantled ground squirrel, and the least chipmunk.

Scan the rocky cliffs for the sure-footed mountain goats. They also frequent the overlook area and hang out near Logan Pass. Bighorn sheep graze in the meadows.

“The Golden-Mantled Squirrel you may very often see

Up in the hills, beside the road, but seldom in a tree.

He looks much like a chipmunk, but examination shows

That his stripes stop at his shoulders, and the chipmunk at his nose.”

From the poem “A Nature Song” by Glacier Ranger Naturalist B.A. Thaxter, 1935

In no time at all, you’ll be taking in the spectacular vistas from the overlook.

Hike Summary

| Total Distance: 2.8 miles |

| Total Elevation Gain: 460 feet; Loss: 95 feet |

| Difficulty*: 3.7, easy (Calculated using Petzoldt’s Energy Rated Mile equation.) |

| Estimated Walking Time: 1 hr 21 min (Calculated using an average speed of 2.5 mph and Naismith’s correction for elevation gain.) |

Optional

The trail continues northwest around the overlook, along the southern flank of Clements Mountain, and then down to the shoreline of Hidden Lake. It’s 2.4 miles round trip from the overlook with a descent of 783 feet. That makes the entire out and back hike from the visitor center 5.2 miles with moderate (7.7) difficulty.

Notes

- Buchholtz, C. W. Man In Glacier. West Glacier, MT: Glacier Natural History Association, Inc., 1976.

- Catton, Theodore, Diane Krahe, and Deidre K. Shaw. “Protecting the Crown: A Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park.” National Park History. Last modified June , 2011. http://npshistory.com/publications/glac/protecting-the-crown.pdf.

- Dyson, James L. The Geologic Story of Glacier National Park. N.p.: The Project Gutenberg, 2019. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/59836/59836-h/59836-h.htm.

- “Examining Visitor Use Trends In Glacier National Park.” Glacier National Park Conservancy. Last modified April 14, 2021. https://glacier.org/newsblog/examining-visitor-use-trends-in-glacier-national-park/.

- “Headwaters (Glacier National Park).” Season 1, Episode 5, Confluence: Logan Pass (podcast), National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 20 Dec. 2020, https://www.nps.gov/podcasts/headwaters.htm.

- Kimball, Shannon Fitzpatrick, and Peter Lesica. Wildflowers of Glacier National Park and Surrounding Areas. Kalispell, MT: Trillium Press, 2010.

- “Logan Pass Opening and Closing Dates.” Glacier National Park. Last modified October 21, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/glac/learn/news/upload/Logan-Pass-Open-Close-Dates_Press-Kit_10-21-20-2.pdf.

- “Park Features Resulting From Glaciation.” National Park History. Last modified July 11, 2008. http://npshistory.com/handbooks/cooperating_associations/glac/2/sec5.htm.

- Seibel, Roberta V. “Logan Pass Wooden Walkway Study.” National Park History. Last modified June 15, 1974. http://npshistory.com/publications/glac/logan-pass-walkway-1974.pdf.